Running Injuries

rduhlir

Posts: 3,550 Member

Time to post a new thread.

Each week I will be posting a new running injury post on this thread. During your running career you will become injured. That is just the nature of the beast. Being able to identify the injury and how to rehabilitate and heal it will help you as you continue on to becoming the stronger, better you. The first topic of discussion will be Iliotibial-Band Syndrome.

Note: I am not a doctor, and all articles that will be posted will include a reference to it. As with any injury, please seek the medical advice from your family doctor, as these are simply informational posts.

Iliotibial-Band Syndrom

Anatomy Lesson

Your iliotibial band (ITB) is a ligament-like structure that starts at your pelvis and runs along the outside of your thigh to the top of your shinbone (tibia). When you run, your ITB rubs back and forth over a bony outcrop on your femur, which helps stabilize it.

Band Aid

If you have poor running mechanics or muscle imbalance, put on weight, or started running hills, then your ITB can track out of line, slipping out of the groove created by the bony outcrop.

Swelling

As it tracks out of its natural alignment, it rubs against other structures inyour leg, creating friction on the band. This results in inflamation (but no swelling) and a click when you bend your knee.

Hold up

The scarring thickens and tightens the ITB, and limits the blood flow to it. If you continue to run, you'll feel a stinging sensation. This can make you limp after a run.

Cause and Effect

Why it happens and how to spot it.

What causes it?

According to research in the Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine, these are the roots of the problems:

>>Inadequate warmup before running.

>>Increasing distance, running too quickly, or excessive downhill running.

>>High or low arches in your feet that cause your feet to overpronate.

>>Uneven leg length.

>>Bowed Legs.

>>Excessive wear on the outside heel edge of a running shoe.

>>Weak hip abductors.

>>Running on a banked surface, such as the shoulder of the road or track.

Spot it!

According to Australian performance coach Carlyle Jekins, you're a likely ITB sufferer if you experience one of the following signs:

>>A sharp or burning pain on the outside of the knee. The symptoms may subside shortly after a run is over, but will return with the next run.

>>You feel tenderness on the outside of your knee if you apply pressure, especially when bending.

>>You may have problems standing on one leg on the affected side, usually due to a weak gluteus medius.

How to rehabilitate it:

Decrease your training load by 50% and apply the principles of R.I.C.E. (rest, ice, compression and elevation), then use some of these:

Donkey Kicks

1. Get on all fours, resting your body weight on your knees and flattening your forearms on the floor into a position similar to that of The Sphinx.

2. Keep your right knee bent as you slowly lift your right leg up behind you to your foot rises toward the ceiling.

3. Hold that position for one second, then slowly return to the start. Perform four sets of 12 reps on each leg.

>>This move strengthens your gluteus maximus and medius, which are vital at keeping your ITB strong.

Laying ITB stretch:

1. Sit on the edge of a bench or firm bed. Lay your torso back and pull the unaffected leg to your chest to flatten your lower back.

2. With your affected leg flat to the bench, maintain a 90-degree bend in that knee. Shift that knee as far inward to the side (towards the other foot) as possible.

3. Hold that position for 30 seconds and repeat four time on each leg.

>>The ITB is difficult to elongate, as it doesn't have nerves that allow you to feel if you're actually stretching it. You might not feel this move in the band but it does isolate it.

Side Laying Clamchell

1. Lie on your side, bending knees and hips to 90 degrees. Wrap a resistance band around your thighs.

2. Lift your top knee up towards the ceiling, making sure that the insides of both feet stay together.

3. Perform 10 to 15 reps, or until you get a burn in the outside of your hip.

>>This move works your gluteus medius (on the outer surface of the pelvis). This muscle prevents your thigh from buckling inward when you run, which is the root of ITB aches.

How long is recovery?

>>Mild: 2-4 weeks

>>Average: 7-8 weeks

>>Severe: 9-24 weeks

Sourse: Willey, David. Runner's World Complete Guide to Running. Emmaus, PA, 2013. Print.

Each week I will be posting a new running injury post on this thread. During your running career you will become injured. That is just the nature of the beast. Being able to identify the injury and how to rehabilitate and heal it will help you as you continue on to becoming the stronger, better you. The first topic of discussion will be Iliotibial-Band Syndrome.

Note: I am not a doctor, and all articles that will be posted will include a reference to it. As with any injury, please seek the medical advice from your family doctor, as these are simply informational posts.

Iliotibial-Band Syndrom

Anatomy Lesson

Your iliotibial band (ITB) is a ligament-like structure that starts at your pelvis and runs along the outside of your thigh to the top of your shinbone (tibia). When you run, your ITB rubs back and forth over a bony outcrop on your femur, which helps stabilize it.

Band Aid

If you have poor running mechanics or muscle imbalance, put on weight, or started running hills, then your ITB can track out of line, slipping out of the groove created by the bony outcrop.

Swelling

As it tracks out of its natural alignment, it rubs against other structures inyour leg, creating friction on the band. This results in inflamation (but no swelling) and a click when you bend your knee.

Hold up

The scarring thickens and tightens the ITB, and limits the blood flow to it. If you continue to run, you'll feel a stinging sensation. This can make you limp after a run.

Cause and Effect

Why it happens and how to spot it.

What causes it?

According to research in the Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine, these are the roots of the problems:

>>Inadequate warmup before running.

>>Increasing distance, running too quickly, or excessive downhill running.

>>High or low arches in your feet that cause your feet to overpronate.

>>Uneven leg length.

>>Bowed Legs.

>>Excessive wear on the outside heel edge of a running shoe.

>>Weak hip abductors.

>>Running on a banked surface, such as the shoulder of the road or track.

Spot it!

According to Australian performance coach Carlyle Jekins, you're a likely ITB sufferer if you experience one of the following signs:

>>A sharp or burning pain on the outside of the knee. The symptoms may subside shortly after a run is over, but will return with the next run.

>>You feel tenderness on the outside of your knee if you apply pressure, especially when bending.

>>You may have problems standing on one leg on the affected side, usually due to a weak gluteus medius.

How to rehabilitate it:

Decrease your training load by 50% and apply the principles of R.I.C.E. (rest, ice, compression and elevation), then use some of these:

Donkey Kicks

1. Get on all fours, resting your body weight on your knees and flattening your forearms on the floor into a position similar to that of The Sphinx.

2. Keep your right knee bent as you slowly lift your right leg up behind you to your foot rises toward the ceiling.

3. Hold that position for one second, then slowly return to the start. Perform four sets of 12 reps on each leg.

>>This move strengthens your gluteus maximus and medius, which are vital at keeping your ITB strong.

Laying ITB stretch:

1. Sit on the edge of a bench or firm bed. Lay your torso back and pull the unaffected leg to your chest to flatten your lower back.

2. With your affected leg flat to the bench, maintain a 90-degree bend in that knee. Shift that knee as far inward to the side (towards the other foot) as possible.

3. Hold that position for 30 seconds and repeat four time on each leg.

>>The ITB is difficult to elongate, as it doesn't have nerves that allow you to feel if you're actually stretching it. You might not feel this move in the band but it does isolate it.

Side Laying Clamchell

1. Lie on your side, bending knees and hips to 90 degrees. Wrap a resistance band around your thighs.

2. Lift your top knee up towards the ceiling, making sure that the insides of both feet stay together.

3. Perform 10 to 15 reps, or until you get a burn in the outside of your hip.

>>This move works your gluteus medius (on the outer surface of the pelvis). This muscle prevents your thigh from buckling inward when you run, which is the root of ITB aches.

How long is recovery?

>>Mild: 2-4 weeks

>>Average: 7-8 weeks

>>Severe: 9-24 weeks

Sourse: Willey, David. Runner's World Complete Guide to Running. Emmaus, PA, 2013. Print.

3

Replies

-

It's amazing how much Pilates will help prevent/rehabilitate running injuries.0

-

As I'm a beginner, do you think yoga can assist in preventing injuries as well?

I'm hoping to be prepared and have little to no injury.

OP, thank you for the great information.1 -

1

-

bump for later0

-

Thank you for posting. I am a newbie to running and am hoping to avoid major injuries, I know things will get hurt eventually, but I really want to get myself established as a runner first.0

-

Hello all....

I have time today to get the next addition of Running Injuries out, so I figure....why not throw it out there. I know I said once a week, but this is an important one to get out there.

Today's topic: Stress Fractures

Next to shin splints, this is probably the most common injury among beginning runners. Why? Because we go out there, we start running, we get that shin splint and ignore it, thinking "Well this is just a beginners ache, it will go away." Next thing we know, we end up with a broken leg. And that is exactly what a stress fracture is...it is a broken bone. Remember that. So here we go....

What are stress fractures?

They are small cracks in a bone that causes pain and discomfort. Simple enough right? It is one of the most overuse injuries out there, even the most experienced runners still get them. It occurs when muscles become fatiqued and are unable to absorb added shock, causing the stress to be forced up on the bone.

Causes:

More often than not, they are the result of increasing the amount of intensity of an activity too rapidly, or by the impact of an unfamilar surface (treadmill to road), improper equipment, and increased physical stress. So, to make it short and sweet...they are caused by doing too much too soon.

Where do they happen?

Most occur in weight bearing bones of the lower legs. The most common places for stress fractures in runners are: the tibia, metatarsals, fibula, and navicular bones.

Women:

Stress fractures can happen in both males and females, but medical research has shown that women are more prone to stress fractures, and many orthopaedic surgeons attribute this to a condition referred to as "the femal athlete triad": eating disorders, amenorrhea, and osteoporosis.

Symptoms:

>>Pain that develops gradually, increases with weight-bearing activity, and diminishes with rest

>>Pain that becomes more severe and occurs during normal, daily activities

>>Swelling on the top of the foot or the outside of the ankle

>>Tenderness to touch at the site of the fracture

>>Possible bruising

Diagnosis:

X-rays are the most common tool for diagnosing stress fractures. But, many times they cannot be seen on regular x-ray films, or will no show up until weeks after symptoms start. Sometimes CT or MRI scans are needed.

Picture of stress fracture in an x-ray:

Treatment:

If you are feeling pain, STOP! Continuing can actually cause the bone to completely break! Remember R.I.C.E.: rest, ice, compression and elevation.

Medical treatment will depend on where the stress fracture is and how bad it is. It could be as simple as limited activity for a few days or even as severe as surgery. But most times the treatment is rest, restrictive footwear and physical theropy.

Sometimes, the stress fracture can be so bad that surgery is needed to correct the issue. Most times this means inserting a type of fastner to help support the bones.

Prevention:

>>Do not increase mileage too fast. Remember, the golden rule: No more than 10% increase per week. This is why the C25K program goes so slow and it is not recommended to skip any weeks. Your body needs the time to adjust to the increased stress. Just because you feel okay, often times your body isn't okay. Let your body recover after each run properly.

>>Cross-train! You can actually do cardio inbetween your C25K days...but don't run. Bike, swim, do the elliptical...or even just walk. You will be accomplishing the fitness goal of cardio, but allowing your body to rest from running (I personally do a HIIT session once a week).

>>Maintain a healthy diet. Make sure you are hitting those calcium and vitamin D micronutrient goals.

>>Use proper equipment...i.e. proper running shoes.

>>If you are having pain, STOP! Remember R.I.C.E. Resume after a few days of rest. Remember, one of the biggest no-nos beginning runners do is ignore aches and pains, thinking it is beginner fatique and it will go away. If it hurts don't keep pushing.

>>Recognize symptoms early, and treat them early. Early treatment can mean the difference between a 6 week or a 4 month recovery.2 -

Hey all....

Today's topic is Shin Splints.

What are Shin Splints?

Known to the medical community as "Tibial Stress Syndrome", shin splints are referred to as pain along or just behind the tibia (shinbone).

What causes them?

>>Excessive force on the shinbone and the connective tissues and muscles. Major contibuting factors include:

~Running downhill

~Running on a slant or tilted surface

~Worn-out footwear

>>Also caused by the "terrible toos"

~Too Hard

~Too Fast

~Too Long

Symptoms

>>Tenderness, soreness, or pain along the tibia.

>>Mild swelling in lower leg.

Risk Factors

>>Being a runner (especially begginers).

>>Flat feet or rigid arches

>>Increased Intensity

Tests and Diagnosis

>>Usually diagnosed on past history. Many times can self diagnos.

>>Medical tests might be needed if pain is severe to rule out stress fractures.

Treatment

>>Yup, you guessed it! R.I.C.E. (Rest, Ice, Compression and Elevation)

>>Rest--avoid the activities that caused the pain. But do not stop exercising. If you develop pain while doing C25K in the form of a shin splint then cross train with an elliptical or bike until the pain has eased, then go back into the program Cross-training will help you keep your aerobic fitness while you allow your legs to heal.

>>Ice--Ice the area for 15-20 minutes four to eight times a day for a few weeks, or until the pain has eased.

>>Reducse Swelling--elevate the leg, and use compression sleeves.

>>Over-the-counter medication--use them to help reduce the pain.

>>Wear proper shoes.

Prevention

>>Wear footwear that is for running. Replace shoes every 300-500 miles.

>>Arch Supports: especially for flat feet.

>>Lessen impact--crosstrain with a sport that places less stress on your shins.

>>Strength train

>>At first sign of pain, stop and rest.

Information sourse: http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/shin-splints/DS002712 -

Plantar Fasciitis

http://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/plantar-fasciitis-topic-overview

What is Plantar Fasciitis?

It is an inflamation of the Plantar Fascia.

The Plantar Fascia is the ligament that runs from your heal bone to your toes. It is what allows you to maintain your arch, and it is the 'shock absorber' in your foot falls. If this ligament becomes strained or injured, the injury is called Plantar Fasciitis.

What Causes it?

Well as stated above, it is an injury to the Plantar Fascia. Repeated injury can actually cause tears in the ligament, and in extreme cases can end up with you in surgury. The most common causes and most prone to this type of this injury are:

>>Your feet roll inward too much when you walk.

>>You have high arches or flat feet.

>>You walk, stand, or run for long periods of time, especially on hard surfaces.

>>You are overweight.

>>You wear shoes that don't fit well or are worn out.

>>You have tight Achilles tendons or calf muscles.

What are the symptoms of Plantar Fasciitis?

If you experience pain with your first few steps in the morning, or after having sat down for a long period of time you might be sufferer of Plantar Fasciitis. Some people have the pain get worse as the day goes on. But, if you don't have right away in the morning, but you develop pain as the day goes on and is worse at night it might be arthritis or a different ailment.

How is it diagnosed?

When you go to the doctor, they will ask you about your prior health, and about your recent exercise attivities. They may take some x-rays to rule out stress fractures or other injuries.

How do I treat it?

Plantar Fasciitis is treated by a number of different ways because people respond differently to different treatments. For some, R.I.C.E. fixes the problem. In some cases, splints might be given to help correct the problem. Sometimes steriod treatments are given. In extreme cases, surgery might be the option. But, surgery is usually reserved for severe cases or for cases in which all other treatment options have not worked.

How before the pain goes away?

Everyone is different. For some weeks, other months or years. It really depends on how bad the injury is and how long you had it before starting treatment.

Do I need to stop?

No, but you will need to reduce your training. The biggest cause of this is overtraining. So if you are developing the problem, go back to the previous week and continue that until your foot has healed. Do not wait! This type of injury can lead to others, causing a chain reaction. Just like shin splints can cause stress fractures, Plantar Fasciitis can cause a world of different issues.

Can I prevent it?

Yes! Taking care of your feet is of course number one. After all, can't run with out them. Well...you can, but that is a different topic of discussion. Wearing shoes that support your arch, or making sure you have inserts that support your arches will help protect your feet.

Do exercises to stretch your Achilles before and defenately after running.

Maintain a healthy weight.

Remember, increase your training load gradually. Maintain the gradual increase concept from C25K as you continue on into your running career.

Alternate running with something else every other day. It is not good to run every day. While yes, some people do it. It is actually smarter to allow your tendons to heal from the stress and cross train with something different. Weight lifting, swimming or biking are all examples of execellent cross training options.

If you are prone to Plantar Fasciitis, barefooting it is a bad idea. Minimalist and barefooting do not offer the arch support needed for people who suffer from this. As soon as you get up, put on supportive shoes. Don't wear flip flops or anything that does not offer good arch support.

What are some stretches I can do at home to help me?

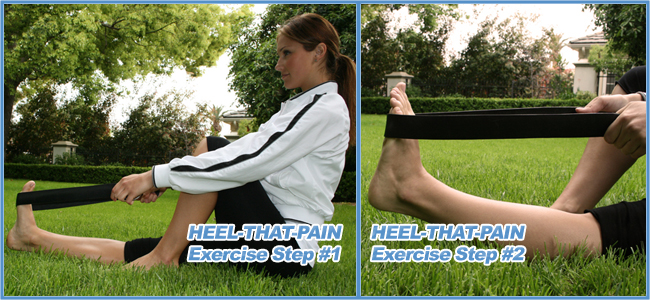

Belt Stretch:

This is an easy one, and you can use a belt, towl, or exercise band. Loop the band around the upper part of your foot and pull into a stretch. (This is a good one for people prone to stress fractures as well)

Incline Board stretch:

Take a book, board or other device and place it on the floor about two feet from the wall. Place the ball of your foot on the device. With your knee straight, lean into the wall keeping your hips and legs in a straight line. Lean in and hold for five seconds. Then do ten to twenty heel raises. Relax and repeat the exercise for a total of ten minutes. Do this with the knee slightly flexed for the same amount of time.

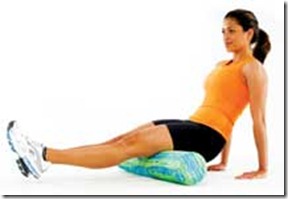

Massage:

Use some type of tubular device placed in the center of the arch. This should be about two inches in diameter and padded. Sitting with your knee bent to ninety degrees begin to gently roll your foot over the massage bar. Increase the pressure until you just begin to feel slight discomfort in the affected area. Maintain that pressure and continue to "roll massage" for 5 to 10 minutes. (You can also use a tennis ball for this)

Stretching:

Stretches for plantar fasciitis requires holding onto a countertop or table and squatting down slowly with the knees bent. The heels of both feet must be kept in contact with the floor while squatting. After 10 seconds, straighten up and relax. The stretch is felt as the heels start to raise off the ground. Repeat this exercise 15-20 times. Stretching the Achilles tendon requires leaning into a wall. Place one leg back behind the other leg. Keep the back knee straight with the heel on the ground while bending the front knee. While leaning forward, the stretch should be felt in the heel cord and foot of the straight leg. Again, after 10 seconds, straighten up and relax. Repeat this exercise 15-20 times with both legs.4 -

Runner's Knee

What is it?

Runner's knee is a broad term that is actually used to describe the a broad spectrum of ailments. It can be caused by many reasons, among them are:

>>Overuse: Repeated bending of the knee can irritate the nerves of the kneecap. Overstretched tendons (tendons are the tissues that connect muscles to bones) may also cause the pain of runner's knee.

>>Direct trauma to the knee, like a fall or blow.

>>Misalignment. If any of the bones are slightly out of their correct position -- or misaligned -- physical stress won't be evenly distributed through your body. Certain parts of your body may bear too much weight. This can cause pain and damage to the joints. Sometimes, the kneecap itself is slightly out of position.

>>Problems with the feet. Runner's knee can result from flat feet, also called fallen arches or overpronation. This is a condition in which the impact of a step causes the arches of your foot to collapse, stretching the muscles and tendons.

>>Weak thigh muscles.

Runner's knee is also called patellofemoral pain syndrome.

Symptoms:

>>Pain behind or around the kneecap, especially where the thighbone and the kneecap meet.

>>Pain when you bend the knee -- when walking, squatting, kneeling, running, or even sitting.

>>Pain that's worse when walking downstairs or downhill.

>>Swelling.

>>Popping or grinding sensations in the knee.

How is it diagnosed?

To diagnose runner's knee, your doctor will give you a thorough physical exam. You may also need X-rays, MRIs (Magnetic Resonance Imaging), CT (Computed Tomography) scans, and other tests.

Treatment:

Regardless of the cause, the good news is that minor to moderate cases of runner's knee should heal on their own given time. To speed the healing you can:

>>Rest the knee. As much as possible, try to avoid putting weight on your knee.

>>Ice your knee to reduce pain and swelling. Do it for 20-30 minutes every 3-4 hours for 2-3 days, or until the pain is gone.

>>Compress your knee. Use an elastic bandage, straps, or sleeves to give your knee extra support.

>>Elevate your knee on a pillow when you're sitting or lying down.

>>Take anti-inflammatory painkillers. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), like Advil, Aleve, or Motrin, will help with pain and swelling. However, these drugs can have side effects, like an increased risk of bleeding and ulcers. They should be used only occasionally, unless your doctor specifically says otherwise.

>>Practice stretching and strengthening exercises if your doctor recommends them.

>>Get arch supports for your shoes. These orthotics -- which can be custom-made or bought off the shelf -- may help with flat feet.

Severe cases of runner's knee may need surgery. A surgeon could take out damaged cartilage or correct the position of the kneecap so that stress will be distributed evenly.

Prevention:

>>Keep your thigh muscles strong and limber with regular stretching.

>>Use orthotics -- inserts for your shoes -- if you have flat feet or other foot problems that may lead to runner's knee.

>>Make sure your shoes have enough support.

>>Avoid running on hard surfaces, like concrete.

>>Stay in shape and keep a healthy weight.

>>Never abruptly increase the intensity of your workout. Make changes slowly.

>>Wear a knee brace while exercising, if you have had runner's knee before.

>>Buy quality running shoes and discard them once they lose their shape or the sole becomes worn or irregular.1 -

Achilles tendinitis

Achilles tendinitis is a common condition that causes pain along the back of the leg near the heel.

The Achilles tendon is the largest tendon in the body. It connects your calf muscles to your heel bone and is used when you walk, run, and jump.

Although the Achilles tendon can withstand great stresses from running and jumping, it is also prone to tendinitis, a condition associated with overuse and degeneration.

Description

Simply defined, tendinitis is inflammation of a tendon. Inflammation is the body's natural response to injury or disease, and often causes swelling, pain, or irritation. There are two types of Achilles tendinitis, based upon which part of the tendon is inflamed.

Noninsertional Achilles tendinitis

Noninsertional Achilles Tendinitis

In noninsertional Achilles tendinitis, fibers in the middle portion of the tendon have begun to break down with tiny tears (degenerate), swell, and thicken.

Tendinitis of the middle portion of the tendon more commonly affects younger, active people.

Insertional Achilles Tendinitis

Insertional Achilles tendinitis involves the lower portion of the heel, where the tendon attaches (inserts) to the heel bone.

In both noninsertional and insertional Achilles tendinitis, damaged tendon fibers may also calcify (harden). Bone spurs (extra bone growth) often form with insertional Achilles tendinitis.

Tendinitis that affects the insertion of the tendon can occur at any time, even in patients who are not active.

Insertional Achilles tendinitis

Cause

Achilles tendinitis is typically not related to a specific injury. The problem results from repetitive stress to the tendon. This often happens when we push our bodies to do too much, too soon, but other factors can make it more likely to develop tendinitis, including:

>>Sudden increase in the amount or intensity of exercise activity—for example, increasing the distance you run every day by a few miles without giving your body a chance to adjust to the new distance

>>Tight calf muscles—Having tight calf muscles and suddenly starting an aggressive exercise program can put extra stress on the Achilles tendon

>>Bone spur—Extra bone growth where the Achilles tendon attaches to the heel bone can rub against the tendon and cause pain

A bone spur that has developed where the tendon attaches to the heel bone.

Symptoms

Common symptoms of Achilles tendinitis include:

>>Pain and stiffness along the Achilles tendon in the morning

>>Pain along the tendon or back of the heel that worsens with activity

>>Severe pain the day after exercising

>>Thickening of the tendon

>>Bone spur (insertional tendinitis)

>>Swelling that is present all the time and gets worse throughout the day with activity

If you have experienced a sudden "pop" in the back of your calf or heel, you may have ruptured (torn) your Achilles tendon. See your doctor immediately if you think you may have torn your tendon.

Doctor Examination

After you describe your symptoms and discuss your concerns, the doctor will examine your foot and ankle. The doctor will look for these signs:

>>Swelling along the Achilles tendon or at the back of your heel

>>Thickening or enlargement of the Achilles tendon

>>Bony spurs at the lower part of the tendon at the back of your heel (insertional tendinitis)

>>The point of maximum tenderness

>>Pain in the middle of the tendon, (noninsertional tendinitis)

>>Pain at the back of your heel at the lower part of the tendon (insertional tendinitis)

>>Limited range of motion in your ankle—specifically, a decreased ability to flex your foot

Tests

Your doctor may order imaging tests to make sure your symptoms are caused by Achilles tendinitis.

X-rays

X-ray tests provide clear images of bones. X-rays can show whether the lower part of the Achilles tendon has calcified, or become hardened. This calcification indicates insertional Achilles tendinitis. In cases of severe noninsertional Achilles tendinitis, there can be calcification in the middle portion of the tendon, as well.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

Although magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not necessary to diagnose Achilles tendinitis, it is important for planning surgery. An MRI scan can show how severe the damage is in the tendon. If surgery is needed, your doctor will select the procedure based on the amount of tendon damage.

Treatment

Nonsurgical Treatment

In most cases, nonsurgical treatment options will provide pain relief, although it may take a few months for symptoms to completely subside. Even with early treatment, the pain may last longer than 3 months. If you have had pain for several months before seeking treatment, it may take 6 months before treatment methods take effect.

Rest. The first step in reducing pain is to decrease or even stop the activities that make the pain worse. If you regularly do high-impact exercises (such as running), switching to low-impact activities will put less stress on the Achilles tendon. Cross-training activities such as biking, elliptical exercise, and swimming are low-impact options to help you stay active.

Ice. Placing ice on the most painful area of the Achilles tendon is helpful and can be done as needed throughout the day. This can be done for up to 20 minutes and should be stopped earlier if the skin becomes numb. A foam cup filled with water and then frozen creates a simple, reusable ice pack. After the water has frozen in the cup, tear off the rim of the cup. Then rub the ice on the Achilles tendon. With repeated use, a groove that fits the Achilles tendon will appear, creating a "custom-fit" ice pack.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication. Drugs such as ibuprofen and naproxen reduce pain and swelling. They do not, however, reduce the thickening of the degenerated tendon. Using the medication for more than 1 month should be reviewed with your primary care doctor.

Exercise. The following exercise can help to strengthen the calf muscles and reduce stress on the Achilles tendon.

>>Calf stretch

Lean forward against a wall with one knee straight and the heel on the ground. Place the other leg in front, with the knee bent. To stretch the calf muscles and the heel cord, push your hips toward the wall in a controlled fashion. Hold the position for 10 seconds and relax. Repeat this exercise 20 times for each foot. A strong pull in the calf should be felt during the stretch.

Physical Therapy. Physical therapy is very helpful in treating Achilles tendinitis. It has proven to work better for noninsertional tendinitis than for insertional tendinitis.

Eccentric Strengthening Protocol. Eccentric strengthening is defined as contracting (tightening) a muscle while it is getting longer. Eccentric strengthening exercises can cause damage to the Achilles tendon if they are not done correctly. At first, they should be performed under the supervision of a physical therapist. Once mastered with a therapist, the exercises can then be done at home. These exercises may cause some discomfort, however, it should not be unbearable.

>>Bilateral heel drop

Stand at the edge of a stair, or a raised platform that is stable, with just the front half of your foot on the stair. This position will allow your heel to move up and down without hitting the stair. Care must be taken to ensure that you are balanced correctly to prevent falling and injury. Be sure to hold onto a railing to help you balance.

Lift your heels off the ground then slowly lower your heels to the lowest point possible. Repeat this step 20 times. This exercise should be done in a slow, controlled fashion. Rapid movement can create the risk of damage to the tendon. As the pain improves, you can increase the difficulty level of the exercise by holding a small weight in each hand.

>>Single leg heel drop

This exercise is performed similarly to the bilateral heel drop, except that all your weight is focused on one leg. This should be done only after the bilateral heel drop has been mastered.

Cortisone injections. Cortisone, a type of steroid, is a powerful anti-inflammatory medication. Cortisone injections into the Achilles tendon are rarely recommended because they can cause the tendon to rupture (tear).

Supportive shoes and orthotics. Pain from insertional Achilles tendinitis is often helped by certain shoes, as well as orthotic devices. For example, shoes that are softer at the back of the heel can reduce irritation of the tendon. In addition, heel lifts can take some strain off the tendon.

Heel lifts are also very helpful for patients with insertional tendinitis because they can move the heel away from the back of the shoe, where rubbing can occur. They also take some strain off the tendon. Like a heel lift, a silicone Achilles sleeve can reduce irritation from the back of a shoe.

If your pain is severe, your doctor may recommend a walking boot for a short time. This gives the tendon a chance to rest before any therapy is begun. Extended use of a boot is discouraged, though, because it can weaken your calf muscle.

Extracorporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT). During this procedure, high-energy shockwave impulses stimulate the healing process in damaged tendon tissue. ESWT has not shown consistent results and, therefore, is not commonly performed.

ESWT is noninvasive—it does not require a surgical incision. Because of the minimal risk involved, ESWT is sometimes tried before surgery is considered.

Surgical Treatment

Surgery should be considered to relieve Achilles tendinitis only if the pain does not improve after 6 months of nonsurgical treatment. The specific type of surgery depends on the location of the tendinitis and the amount of damage to the tendon.

Gastrocnemius recession. This is a surgical lengthening of the calf (gastrocnemius) muscles. Because tight calf muscles place increased stress on the Achilles tendon, this procedure is useful for patients who still have difficulty flexing their feet, despite consistent stretching.

In gastrocnemius recession, one of the two muscles that make up the calf is lengthened to increase the motion of the ankle. The procedure can be performed with a traditional, open incision or with a smaller incision and an endoscope—an instrument that contains a small camera. Your doctor will discuss the procedure that best meets your needs.

Complication rates for gastrocnemius recession are low, but can include nerve damage.

Gastrocnemius recession can be performed with or without débridement, which is removal of damaged tissue.

Débridement and repair (tendon has less than 50% damage). The goal of this operation is to remove the damaged part of the Achilles tendon. Once the unhealthy portion of the tendon has been removed, the remaining tendon is repaired with sutures, or stitches to complete the repair.

In insertional tendinitis, the bone spur is also removed. Repair of the tendon in these instances may require the use of metal or plastic anchors to help hold the Achilles tendon to the heel bone, where it attaches.

After débridement and repair, most patients are allowed to walk in a removable boot or cast within 2 weeks, although this period depends upon the amount of damage to the tendon.

Débridement with tendon transfer (tendon has greater than 50% damage). In cases where more than 50% of the Achilles tendon is not healthy and requires removal, the remaining portion of the tendon is not strong enough to function alone. To prevent the remaining tendon from rupturing with activity, an Achilles tendon transfer is performed. The tendon that helps the big toe point down is moved to the heel bone to add strength to the damaged tendon. Although this sounds severe, the big toe will still be able to move, and most patients will not notice a change in the way they walk or run.

Depending on the extent of damage to the tendon, some patients may not be able to return to competitive sports or running.

Recovery. Most patients have good results from surgery. The main factor in surgical recovery is the amount of damage to the tendon. The greater the amount of tendon involved, the longer the recovery period, and the less likely a patient will be able to return to sports activity.

Physical therapy is an important part of recovery. Many patients require 12 months of rehabilitation before they are pain-free.

Complications. Moderate to severe pain after surgery is noted in 20% to 30% of patients and is the most common complication. In addition, a wound infection can occur and the infection is very difficult to treat in this location.1 -

bump0

-

Muscle Pulls

These of course we will focus on the legs, but remember the muscle pulls can happen anywhere on your body. Anything that is attached to your core can be pulled when running.

So before we get into the causes of pulls and what they are we need a little bit of an anatomy lesson. There are 3 types of mucles in the body:

-cardiac

-smooth

-voluntary skeletal muscles.

The skeletal muscles are what make up the majority of the muscles in your body. These are the muscles you can control and what allow you to run that 5K. The muscles are attached to your bones via tendons. These muscles are made of bundles of fibers that are designed to contract. When the fibers contract, the muscle shortens, pulling on the attached bone and rotating the bone about the joint.

Often times, during this contraction, the muscle fibers encounter resistance. This can be because the muscle is being used to lift something (like a weight in the case of a bicep curl). Resistance can also come from the ground, which is what creates the ability to run, jump, cut to switch directions, etc.

The problem arises when the resistance is strong or sudden enough to be too much for the muscle fibers to handle. In such a case, in the attempt to contract against this resistance, the muscle fibers tear. If enough of the fibers tear, you end up with a muscle strain or pulled muscle and its associated muscle pain. Medical aid is usually necessary when healing torn muscle injuries.

Symptoms

When you pull a muscle, blood vessels within the muscle tissue are torn, which damages the circulation to and from the area. Without a proper pathway, fluids “spill” into the muscle tissue, causing swelling and on occasion bruising. Sometimes these fluids may cause the area to visibly swell, but more commonly the result is internal inflammation. This inflammation is the root of pain.

In addition to pain and possible swelling, a muscle pull is usually accompanied by a lack of function.

Treatment

If you have sustained a muscle strain, here are some muscle treatment options:

Rest. If you can, resting is very good for muscle recovery with one caveat. Rest is only good if the muscle pull recovery process is already underway.

What does this mean? We had a call from an athlete recently exclaiming a common problem. “I sustained a pulled quad three weeks ago, and I’ve been resting, but it is still bothering me, and it is very tight.”

In this case, and in many cases, an injured body part is getting rest, but not recovering. Why? The injured body part is essentially shut down. Circulation is impaired, and pain or a muscle spasm persists for a long period of time. The healing process is stuck.

When this is the case, it’s like a car accident on a freeway – nothing can move. If you don’t have a tow truck to clear some wreckage, you can wait as long as you want, but the traffic remains jammed.

Rest is good once the body’s healing ability is enabled. Then the body can leverage the time, using it to assist recovery.

Ice.

Perhaps the most commonly suggested method for pulled muscle recovery is icing. It is often prescribed with compression and elevation as R.I.C.E, which stands for rest, ice, compression and elevation.

The most beneficial time to ice is in the first 36-48 hours after the muscle pull. Initially, ice can help lessen swelling by cooling the injured tissue, which slows local circulation and fluid build-up. You want to try to keep swelling down, because a swollen muscle (or joint) does not heal well.

If you use ice, don’t do so for more than 15 minutes at a time, and keep moving the ice around a bit. If you ice for longer periods of time, you can chill your skin enough to get frostbite, which of course you don’t want!

Like many things, ice’s greatest strength is also its greatest weakness. Remember, ice slows circulation to your injury, which limits swelling. That’s good. However, circulation is what removes waste materials from damaged body tissue, and brings in oxygen and nutrients needed for repair – all of which are essential for healing. Ice slows this process, which is not good.

So ice is a double-edged sword. As long as you use it appropriately, in the initial stages of an injury or to calm inflammation or swelling, you should be OK.

Advantages: Free, all-natural, readily available, limits swelling.

Disadvantages: Slows circulation, needs to be carefully administered.

Heat. As you might expect, if ice slows circulation, heat increases it. Heat is not a good idea in the initial period after a muscle pull. Heat will tend to increase swelling, which will slow down the healing process.

So when should I apply heat? Once your muscle pull is feeling better, you can consider using heat to help warm up the muscle prior to exercise. The most common way is a hot water pack or a moist, wet towel.

Advantages: Free, all-natural, readily available, increases circulation.

Disadvantages: Can aggravate inflamed or swollen tissue. Do not use in the initial stages of injury recovery.

NSAIDS. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatories are another common method of recovery. If you don’t recognize the term, you’re no doubt familiar with their common names: aspirin, ibuprofen, naproxen, etc.

You take them in pill form, and they initially help to reduce inflammation. After this initial effect, the main action is to inhibit pain signals in the brain. In other words, your injury is still sending signals, but your brain is not listening.

The initial anti-inflammatory action can be good. The pain relief is usually beneficial as well, because no one likes pain. But realize that in essence you are killing the messenger; not addressing the root of the problem.

Generally speaking, inhibiting brain/body communication isn’t the best approach to health. NSAIDS can also have some side effects if you use them consistently. Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, rashes and headaches are some of the most common. On the more serious side, they may elevate chances of kidney failure, liver failure and ulcers.

Cost: Typically Minimal

Advantages: Can have initial anti-inflammatory effects, and can inhibit pain transmitters in the brain.

Disadvantages: After initial effects, do not help injury directly. Some serious side effects from continuous use.

Ultrasound. Some professionals will employ ultrasound, and you can purchase a machine to do it on your own. Ultrasound is a form of heat therapy that uses high-frequency sound waves (that are too high to hear) to vibrate soft tissue. This heats the tissue. The intent is to promote circulation, which is essential for healing.

While ultrasound has been shown to help warm up and increase range of motion prior to physical activity in a non-injured joint, studies have yet to suggest results for most sports injury recovery. Despite this, it has recently become a fairly popular thing to do.

You can get a home ultrasound machine, but more typically it is administered by a trained professional. This is especially true for children under the age of 16, who should only receive ultrasound by a professional. There are a few cautions, in that you don’t want to use ultrasound over internal organs or areas that may be infected. Sports injury ultrasound should not be used by pregnant women.

Cost: $50 plus for a 15-minute session. $400 for a home unit.

Advantages: Helps warm tissue, which may increase circulation.

Disadvantages: Should typically be administered by a professional, which means scheduling an appointment.

Herbal Wraps. What are they? An herbal paste or plaster is wrapped onto the injury and worn for 12 hours, then discarded. Gaining recognition among pro and amateur athletes in the United States, these properly formulated East Asian herbal wraps have been known for centuries to help the body recover from muscle strains. When you sustain a pulled muscle, your body’s ability to circulate energy is interrupted and becomes imbalanced. In many cases, the affected area will essentially “shut down”, feeling both weak and painful. These wraps function by promoting energy circulation and by removing toxins that can inhibit recovery processes.

Doctor, chiropractor or acupuncturist. Aside from the above self-treatment options, you can visit a practitioner, such as a doctor, chiropractor or acupuncturist. If you suspect that your injury is serious, it is a good idea to have it checked out by a doctor. Signs that your injury is serious include excessive or sharp pain, numbness, a lot of swelling and/or a minimal range of motion.

The obvious benefit of finding an expert is that you can get a specific diagnosis. Often the prescribed pulled muscle treatment is one of the methods described above. Often the cost will be covered by health insurance, although you can be responsible for a co-payment.

Prevention

1. Make sure you have strength AND flexibility. Sometimes as athletes we build strength, but neglect flexibility. Or, we develop flexibility by don’t put as much emphasis on strength. When you favor one over the other, you create imbalance that can lead to injury. A strong muscle that is tight lacks the suppleness to handle a sudden muscle strain, and muscle fibers tear. A flexible muscle is suddenly put to the test, and lacks the strength to hold its own, also resulting in a muscle pull.

2. Train to develop strength and ability in many directions. Too often athletes practice only what they need to for a particular sport. When you do this, you develop certain abilities (for example sprinting acceleration), but leave behind other skills (for example the ability to move laterally). When you favor one set of muscle fibers over another, one part is developed and the other part is under-developed by comparison. A sudden motion that exposes the under-developed muscles results in a muscle strain or pull.

3. Warm up. Everyone has heard of this one, but too often it is not done the right way. A cold rubber band is less elastic than a warm one, and your muscles are no different. Do not start by stretching them – this is not a good approach. Start by moving around – break a light sweat. At this point you can go through some stretching. In general it is better to stretch after your training than before. The body is warm, your muscles are more elastic, and stretching at this time helps to develop flexibility, which most athletes need.

4. Recover on daily basis. The key to preventing the onset of a fatigue injury or a chronic muscle injury is to allow your muscles to recover after daily practice. If you don’t, sooner or later your body will lose the battle and you will find yourself with an injury. Rest is key. Proper warm-downs are a good way to reduce shock to the body. We also recommend certain topical formulas available from a company called Chi Herbal. These sprays and soaks have been quite good for helping athletes’ recover from competition or daily training quickly.1 -

One of the biggest factors in knee pain is overstriding and heel striking. The way to overcome this is increasing your cadence. Here's a great article on the topic: http://www.runnersworld.com/running-tips/pick-beat2

-

Great topic! Thanks, Rebecca!!!0

-

I've just read through this thread and think I have suffered from most of these at one time or another! And not all from running, I bought a pair of comfortable shoes for walking to work and they gave me plantar fasciitis.0

-

Any thoughts on doing some weight training or other cardio in addition to following the C25K program? Id like to work on toning up and improve overall physical fitness but feel that 90 minutes of walking/jogging a week just isn't enough. Is anyone else supplementing the C25k program with other activities?0

-

Any thoughts on doing some weight training or other cardio in addition to following the C25K program? Id like to work on toning up and improve overall physical fitness but feel that 90 minutes of walking/jogging a week just isn't enough. Is anyone else supplementing the C25k program with other activities?

I do Stronglifts and I know some people do NROLFW, which is good for your core and legs. Cross training on your non-running days is a great way to balance out your running, swimming and cycling are popular, but try to keep it low impact to give your legs a rest. And make sure you have at least one full rest day a week.1 -

You can certainly do weight training while doing C25K. Find a strength program that fits your life style. Yoga/Pilates is a good strength/stretch exercise to use as strength training.

You can also do more cardio, just make sure that any cardio you choose does not interfere with your recovery from C25K. So think low impact. Biking, swimming, walking. It should be equal to what you are doing now, so 30 minute segments.1 -

info to keep0

-

Anyone ever hurt their peroneus (or fibularis) muscles/tendons?

I think that's what I've injured. I completed the 3rd run of Week 5 in C25K and, during my cool down walk, I got this stabbing pain above my ankle toward the outside back of my calf. Nothing traumatic happened during the run and there was no swelling or anything like that. I suspect it could be due to the uneven/cambered trail I run on in the park. That was last Sunday and I haven't been able to fully do a calf stretch since without a prickly, sharp, stabbing feeling in that area that occasionally radiates to the back center of my leg just beneat the calf.

Standing on the toes makes it feel better and springing off the foot while walking seems to be the most uncomfortable part. Stairs are tricky and makes it feel worse. :frown:

Running became such a great stress-reliever after getting over the initial hump and I'm really bummed that I've had to stop (though I'm SO tempted to try). I wonder if anyone on MFP has any suggestions on how not to lose the progress I've made over the last weeks? I saw that one recommendation was elliptical training. I can try that, and anything else that won't hurt my leg (or maybe help it) that I can do?

Thanks so much for any suggestions or recommendations.0 -

Anyone ever hurt their peroneus (or fibularis) muscles/tendons?

I think that's what I've injured. I completed the 3rd run of Week 5 in C25K and, during my cool down walk, I got this stabbing pain above my ankle toward the outside back of my calf. Nothing traumatic happened during the run and there was no swelling or anything like that. I suspect it could be due to the uneven/cambered trail I run on in the park. That was last Sunday and I haven't been able to fully do a calf stretch since without a prickly, sharp, stabbing feeling in that area that occasionally radiates to the back center of my leg just beneat the calf.

Standing on the toes makes it feel better and springing off the foot while walking seems to be the most uncomfortable part. Stairs are tricky and makes it feel worse. :frown:

Running became such a great stress-reliever after getting over the initial hump and I'm really bummed that I've had to stop (though I'm SO tempted to try). I wonder if anyone on MFP has any suggestions on how not to lose the progress I've made over the last weeks? I saw that one recommendation was elliptical training. I can try that, and anything else that won't hurt my leg (or maybe help it) that I can do?

Thanks so much for any suggestions or recommendations.

Ice it and stretch your calf muscles.0 -

OK, I bought a new pair shoes.went running outside yesterday and all was well.no problems with my shin splints, but today did the same routine on the treadmill ,:noway shin splints are hurting like crazy . What gives. can anybody explain to me why the difference . :noway:0

-

OK, I bought a new pair shoes.went running outside yesterday and all was well.no problems with my shin splints, but today did the same routine on the treadmill ,:noway shin splints are hurting like crazy . What gives. can anybody explain to me why the difference . :noway:

Don't know. I have the same issues. I try to make sure I'm not heel striking, but I'm a little more sore when I do the treadmill.1 -

LOVE this thread!!! Thank you for the very useful info!0

-

I think I pulled a muscle in my hip during my last run. I noticed pain after I finished and was doing my cool down walk. It hurt for about 2 days, then seemed to subside. I was pain free today, then when I started my run I immediately felt the pain there again. It lasted about 15 seconds. Then it either subsided or I blocked it from my mind because it was painful again after my run and still is now several hours later. Mostly when I get up from a sitting position.

I don't know if there are any doctors or physiotherapists here, but it hurts when I lean down sideways towards the affected side. I feel more of a stretch when I lean down away from the affected side. I am going to physio tomorrow anyway so will make sure I mention it, I will probably be able to get some treatment on it right away.

Just wondered though, if anyone else has experienced an injury like this.0 -

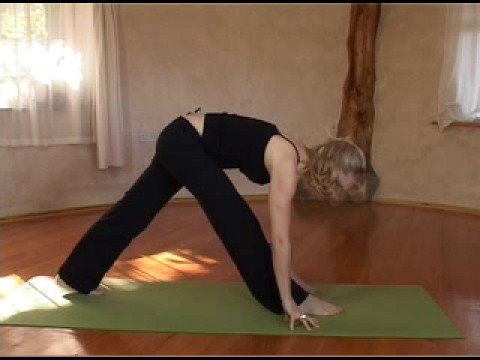

Sounds like you have bursitis, an inflammation of the fluid-filled sacs that lubricate your joints. Usually that is caused by tight hamstrings or an inflamed IT band. After your warm up walk, briefly stretch your hamstrings and IT band.

For the hamstrings:

For the IT band:

For the hips:

After your runs make sure you really focus on the stretching. You really should do each stretch you do twice. The first rep is to just loosen the muscle, that is the one you hold the longest but no more than 25-30 seconds. The second rep you hold for only 15 seconds, but you go deeper into the stretch. You stop at the thresold, which means any further and the stretch would be painful. That second rep should be uncomfortable but no pain.

When you get home, take an anti-inflammatory and ice in the general area where the pain is. Then later that night, or after icing (or both, lol), use a foam roller to roll out the area. It will hurt and you will curse that hard piece of foam...but oh the wonders a foam roller does!

IT Band:

Hamstrings:

Hip Flexor: 0

0 -

What about pain on the top outside edge of your foot? I've been dealing with that for a few days and debating whether it's a new runner/fat/out of shape thing, or something more serious I need to see a doctor about.1

-

Pain on the top of your foot the way you describe sounds like impoper footwear or laces too tight. If you research different ways to tie your shoes you might be able to find a way that will help with the issue.1

-

Thanks for the stretching info, the photos are especially helpful!0

-

I think I pulled a muscle in my hip during my last run. I noticed pain after I finished and was doing my cool down walk. It hurt for about 2 days, then seemed to subside. I was pain free today, then when I started my run I immediately felt the pain there again. It lasted about 15 seconds. Then it either subsided or I blocked it from my mind because it was painful again after my run and still is now several hours later. Mostly when I get up from a sitting position.

I don't know if there are any doctors or physiotherapists here, but it hurts when I lean down sideways towards the affected side. I feel more of a stretch when I lean down away from the affected side. I am going to physio tomorrow anyway so will make sure I mention it, I will probably be able to get some treatment on it right away.

Just wondered though, if anyone else has experienced an injury like this.

Bursitis in the hip can cause a pain, usually more intense after you are done running. For me it was more of a tightness with a almost burning pain right where your butt=side meets your hip. The only way I can control it was to stop running for about 2 weeks, started a weight training program that focused on my core and legs, and very gradually started running again slowly and only a couple miles at a time. Did that for at least 2 months. Still doing the strength training also0

This discussion has been closed.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PjGlXtbKCPg

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PjGlXtbKCPg