Obesity, Processed Foods, and Positing That “Extra Exercise” Can Eventually Hit a Metabolism Wall

Washington Post 7-15-2025

What causes obesity? A major new study is upending common wisdom.

Many people assume obesity is caused by too little exercise and too many calories. But researchers have found inactivity is not the main cause.

Obesity is uncommon among Hadza hunter-gatherers in Tanzania, Tsimane forager-farmers in Bolivia, Tuvan herder-farmers in Siberia, and other people in less-developed nations. But it’s widespread among those of us in wealthy, highly industrialized nations.

Why? A major study published this week in PNAS brings surprising clarity to that question. Using objective data about metabolic rates and energy expenditure among more than 4,000 men and women living in dozens of nations across a broad spectrum of socioeconomic conditions, the study quantified how many calories people from different cultures burn most days.

For decades, common wisdom and public health messaging have assumed that people in highly developed nations, like the United States, are relatively sedentary and burn far fewer daily calories than people in less-industrialized countries, greatly increasing the risk for obesity.

But the new study says no. Instead, it finds that Americans, Europeans and people living in other developed nations expend about the same number of total calories most days as hunter-gatherers, herders, subsistence farmers, foragers and anyone else living in less-industrialized nations.

That unexpected finding almost certainly means inactivity is not the main cause of obesity in the U.S. and elsewhere, said Herman Pontzer, a professor of evolutionary anthropology and global health at Duke University in North Carolina and a senior author of the new study.

What is, then? The study offers provocative hints about the role of diet and some of the specific foods we eat, as well as about the limits of exercise, and the best ways, in the long run, to avoid and treat obesity.

Is diet or inactivity causing obesity?

“There’s still a lively debate in public health about the role of diet and activity” in the development of obesity, Pontzer said, especially in wealthy nations. Some experts believe we’re exercising too little, others that we’re eating too much, and still more that the two contribute almost equally.

Understanding the relative contributions of diet and physical activity is important, Pontzer noted, because we can’t effectively help people with obesity unless we first tease out its origins. But few large-scale studies have carefully compared energy expenditure among populations prone to obesity against those more resistant to it, which would be a first step toward figuring out what drives weight gain.

So, for the new study, Pontzer and his 80-plus co-authors gathered existing data from labs around the world that use doubly labeled water in metabolism studies. Doubly labeled water contains isotopes that, when excreted in urine or other fluids, allow researchers to precisely determine someone’s energy expenditure, metabolic rates and body-fat percentage. It’s the gold standard in this kind of research.

They wound up with data for 4,213 men and women from 34 countries or cultural groups, running the socioeconomic gamut from tribes in Africa to executives in Norway. They calculated total daily energy expenditures for everyone, along with their basal energy expenditure, which is the number of calories our bodies burn during basic, biological operations, and physical activity energy expenditure, which is how many calories we use while moving around.

A new theory of how our metabolisms work

After adjusting for body size (since people in wealthy nations tend to have larger bodies, and larger bodies burn more calories), they started comparing different groups. Anyone expecting a wide range of energy expenditures, with hunter-gatherers and farmer-herders at the high end and deskbound American office workers trailing well behind, would be wrong.

Across the board, the total daily energy expenditures of the 4,213 people were quite similar, no matter where they lived or how they spent their lives. Although the hunter-gatherers and other similar groups moved around far more throughout the day than a typical American, their overall daily calorie burns were nearly the same.

The findings, though counterintuitive, align with a new theory about our metabolisms, first proposed by Pontzer. Known as the constrained total energy expenditure model, it says that our brains and bodies closely monitor our total energy expenditure, keeping it within a narrow range. If we start consistently burning extra calories by, for instance, stalking prey on foot for days or training for a marathon, our brains slow down or shut off some tangential biological operations, often related to growth, and our overall daily calorie burn stays within a consistent band.

The role of ultra-processed foods

The upshot is that “there is no effect of economic development on size-adjusted physical activity expenditure,” Pontzer says. In which case, the fundamental problem isn’t that we’re moving too little, meaning more exercise is unlikely to reduce obesity much.

What could, then? “Our analyses suggest that increased energy intake has been roughly 10 times more important than declining total energy expenditure in driving the modern obesity crisis,” the study authors write.

In other words, we’re eating too much. We may also be eating the wrong kinds of foods, the study also suggests. In a sub-analysis of the diets of some of the groups from both highly and less-developed nations, the scientists found a strong correlation between the percentage of daily diets that consists of “ultra-processed foods” — which the study’s authors define as “industrial formulations of five or more ingredients” — and higher body-fat percentages.

We are, to be blunt, eating too much and probably eating too much of the wrong foods.

“This study confirms what I’ve been saying, which is that diet is the key culprit in our current [obesity] epidemic,” said Barry Popkin, a professor at the Gillings School of Global Public Health at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and an obesity expert.

“This is a well-done study,” he added.

Other experts agree. “It’s clear from this important new research and other studies that changes to our food, not our activity, are the dominant drivers of obesity,” said Dariush Mozaffarian, director of the Food is Medicine Institute at Tufts University in Boston.

The findings don’t mean, though, that exercise is unimportant, Pontzer emphasized. “We know that exercise is essential for health. This study doesn’t change that,” he said.

But the study does suggest that “to address obesity, public health efforts need to focus on diet,” he said, especially on ultra-processed foods, “that seem to be really potent causes of obesity.”

Gretchen Reynolds is the author of the "Your Move" column for The Washington Post. Reynolds is an award-winning journalist who has been writing about the science of exercise and health for more than 15 years, first at the New York Times and now at The Post.

Replies

-

Many interesting points, including that simply increasing exercise (guilty!) eventually hits a metabolic wall and fails to work.

0 -

That unexpected finding almost certainly means inactivity is not the main cause of obesity in the U.S. and elsewhere…

While I have my own opinions on which is more important, exercise vs diet, I disagree with this logical assumption made in the article, which claims that because energy burn is almost identical, it must logically mean it doesn't matter. One statement does not require the other to be true; they MAY be, but not HAVE to be.

2 -

Ponzer et. al. have been on this theme since at least 2015, comparing Hadza energy expenditure to developed-world energy expenditure. Maybe they do have a "new study" adding to that literature, but the WaPo contention that this is upsetting conventional wisdom in 2025 is IMO just clickbait. Maybe it's upsetting people who haven't heard about it before, but that's about popular attention span more than it's about any form of "wisdom" IMO.

I have various problems with the article's conclusions from my not-an-expert perspective. (Of course I'm seeing it through the lens of my own biases. I can't not. 😆)

For one, the "horrors of ultra-processed food" take is seemingly still mostly just a correlation. Is it in the mix? Sure, probably.

But speaking as someone who's been adult for the whole of the "obesity crisis" developing, I think it's multi-factorial. For sure, there are cultural factors. The norms around food and eating have changed very noticeably in that time period. Some of those changes may flow from the fact that many people find ultra-processed foods tempting but not filling, sure. But the norms also matter.

Example norm: In my young adulthood, it wasn't normal to be carrying around and sipping on a calorie-dense beverage in every social context from home, to work, to driving in one's car. Cars didn't have cupholders, let alone more cupholders than their average number of passengers, and the sole reason wasn't the stupidity of car makers even as people routinely put cups in their laps or something. Further, in most locales, a person couldn't go out and buy those beverages pre-made 24x7 at nearly every crossroads gas station, convenience store, fast food joint, coffee chain, etc. I'm not saying everyone does this these days: I'm saying no one really questions it, because it's "normal".

That's just one other factor. There are more others I won't belabor here.

A bigger problem I have with the study conclusions is how it's reported. Absolutely, governments and health organizations need to focus on population trends and their public health implications. But at the level of individual actual people, there's variability in behavior and consequences.

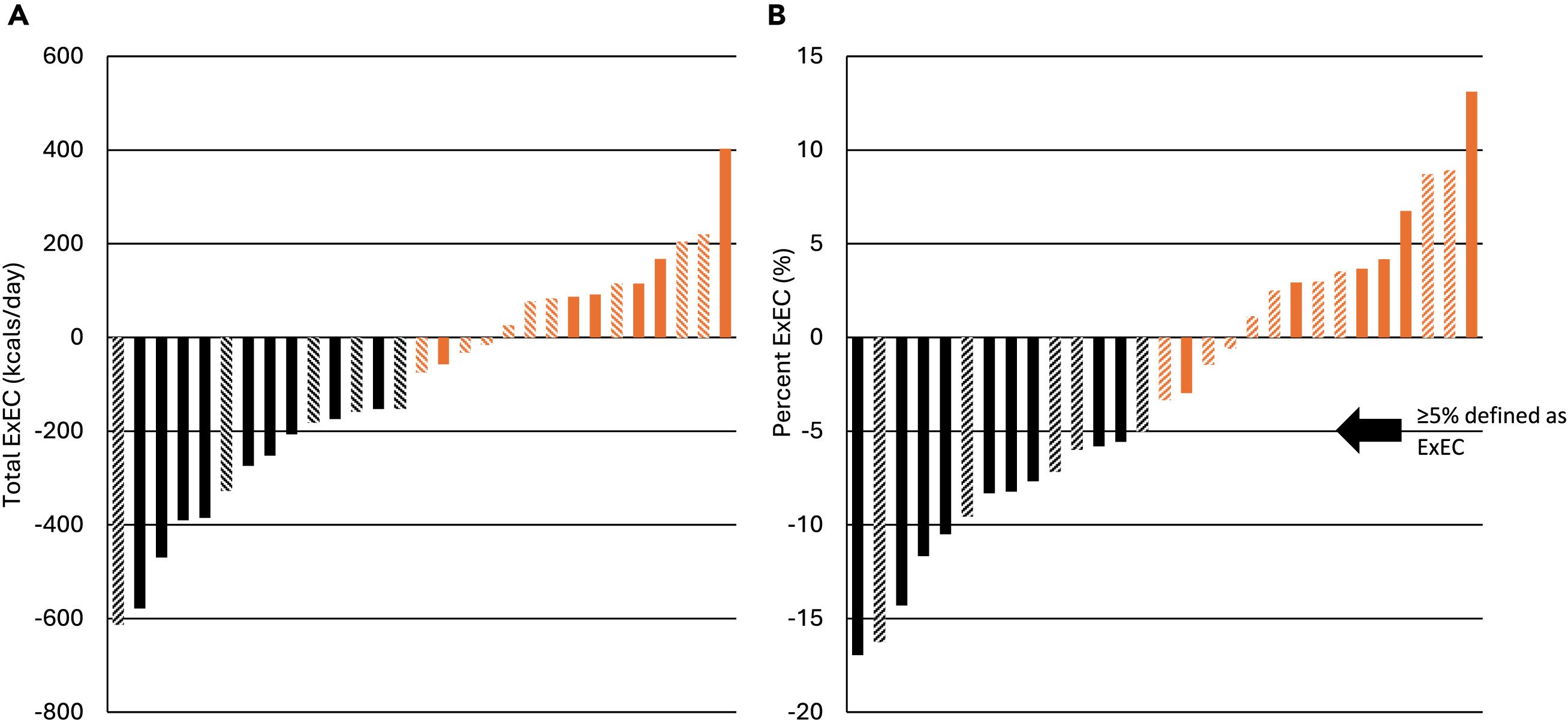

Example: Energy compensation (a.k.a. calorie compensation) is a thing. It's relevant in the study in question. When we study groups of people, the reasonable conclusions are that when people exercise more, they compensate for that exercise by burning fewer calories in daily life. They don't get the total benefit of the exercise calories as an add-on to TDEE. But that's when you look at groups.

As the studies take a more fine-grained look, they start to conclude that there are "compensators" and "non-compensators". That is, for some people, a lot of the exercise calories seem to be an add-on to TDEE (they're "non-compensators"), and for other people, the exercise calories increase TDEE much more negligibly ("compensators").

Take that down even further into the details, some studies - admittedly small so far, at least the ones I've seen - suggest that it's more like a continuous spectrum with compensators at one end, non-compensators at the other, and the individuals studied arrayed somewhat evenly across the whole range in between.

Just for funsies, this is a graphic I posted in the "Does a Higher Calorie Allowance Make Managing Weight Loss Easier or Harder" thread here in Debate Club:

Caption for that graphic from the original article: "Exercise-related energy compensation (ExEC) expressed as (A) Absolute ExEC (kcals/day) and (B) Percent ExEC. Black indicates energy compensation, and orange bars indicate no energy compensation."

That's the range of compensators/non-compensators in one small study. It's about a 1000 calorie range! The original source is here:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2589004224010642

I typed more about that in my post, which is here:

So, sure, Pontzer et. al.'s study is not wrong, and is relevant at the public-policy level.

(The jump to just "ultra-processed food" may be a bit quick, but sure, it's tempting to many and tends to be non-filling. Some will cite Hall et. al.'s study of macro-matched processed and less-processed eating plans as evidence that it's the ultra-processed foods, and there's some evidence there; but there was quite a long discussion here some time back about that study, with a lot of questioning whether the less-processed diets had people consume fewer calories because they were more filling or less tasty. Maybe it doesn't matter.)

But if we're translating those Pontzer et. al. study results into advice for other individuals - and action for ourselves - things get a little more complicated, if you ask me.

To me, at the n=1 advice level, it still boils down to recommending finding one's own best eating routine for satiety, nutrition and calorie-appropriateness; one's own best well-balanced-life activity routine (exercise and daily life); and running the n=1 4-6 week experiment to validate one's personal calorie needs in context of one's activity/eating routine.

No matter what I/we think about weight loss, I feel like there's always more to it than that . . . whatever the "that" is. 😆

3 -

I'll advance an unsupported out of my kitten "vibe" type theory 🤣

To some degree we all compensate.

Less food available and more exercise applied.... higher efficiencies, more "marginal" (till they bite you in the kitten) processes suppressed. Hey there's even people who are trying to create metabolic slowdown for longevity.

More food and less exercise and we are out in 32F/0C in shorts and sandals.

Both imaginary individuals consumed 3500 Cal today and achieved energy balance 🤣

One collapsed on the hut's floor after getting water from the river using a clay pot three times today because the wife got her yearly half day off for her birthday; the other went out to 7-11 to get a Slurpee in the snow to show off his new shorts and sandals.

Same TDEE and intake mind you!🤣

If you want to run it a bit more (and this is still "vibe" level cause I'm sure I've run into it but haven't double checked it for support), it seems a common finding that most obese individuals are / were at the higher than expected side of tdee based on their activity; not the lower side of it as we often believe as a cause of gaining weight

If that is actually the case it can account for some of this even if you then average to a common comparison weight.

I.e. metabolic increase from overeating vs decrease from overexertion with limiting nutritional support.

/talking out of my kitten

1 -

@PAV8888 -

Admittedly cherry-picking from

https://www.mdpi.com/2079-9721/13/2/55

When people spend extended periods in physically inactive postures—such as prolonged sitting—NEAT naturally decreases, contributing to a sustained positive energy balance. Studies in both lean and obese populations consistently show that individuals with obesity tend to have lower baseline NEAT, in part because of an increased inclination toward sedentary behaviors.

I'm not saying that negates your saying that

it seems a common finding that most obese individuals are / were at the higher than expected side of tdee based on their activity

because NEAT is not TDEE, but it's relevant, I think. I've read that in various places, though don't have diverse cites at my fingertips. From memory, I think I read something saying that the "lower NEAT" idea remained true in formerly obese people (in statistically averaged terms) even after they lost weight, and might account for some part of the common tendency to regain.

0 -

The second part (in formerly obesse) would be part of the long term metabolic adaptation argument (how long term, does it resolve, how and when.)

Re your main correction: I guess that it does appear to equalize on fat free mass basis so strictly speaking RMR is lower per lb of total mass (on a quick search)🤷🏼♀️ so you are correct in your correction!🤣

0 -

I'm not sure that post-loss it's just part of the long term metabolic adaptation. It's been a while since I read about it, but I remember - possibly remember inaccurately - the finding as being that as a statistical average obese people were actually more placid and sedentary in daily life movement, and remained more placid/sedentary behaviorally even after weight loss. IOW, I think the argument was that some people's habits of movement are different, and the habits don't change just because they're lighter.

Again, statistically - averages, not necessarily each and every individual.

0 -

so eat less and maximize diet for better nutrition?

0 -

But also … pro cyclists will eat 5,000 calories a day, sometimes more. When I was doing a lot of training and racing (around 400+ miles a week) as an amateur, my weight dropped, even though I was eating about 5 times as much as I do now (I still exercise quite a bit).

There is likely a threshold of effort and during that when crossed, we will lose weight. Also, to keep up the volume of exercise, we need to adjust to the right kind of food to fuel our bodies.

0 -

I am convinced that that "Hadza hunter-gatherers in Tanzania, Tsimane forager-farmers in Bolivia, Tuvan herder-farmers in Siberia, and other people in less-developed nations" are not making themselves crazy worrying about their "obesity".

0

Categories

- All Categories

- 1.4M Health, Wellness and Goals

- 398.1K Introduce Yourself

- 44.7K Getting Started

- 261K Health and Weight Loss

- 176.4K Food and Nutrition

- 47.7K Recipes

- 233K Fitness and Exercise

- 462 Sleep, Mindfulness and Overall Wellness

- 6.5K Goal: Maintaining Weight

- 8.7K Goal: Gaining Weight and Body Building

- 153.5K Motivation and Support

- 8.4K Challenges

- 1.4K Debate Club

- 96.5K Chit-Chat

- 2.6K Fun and Games

- 4.8K MyFitnessPal Information

- 12 News and Announcements

- 21 MyFitnessPal Academy

- 1.5K Feature Suggestions and Ideas

- 3.2K MyFitnessPal Tech Support Questions